Design patterns reviewed #2: structural

This is the second post in a series in which I’m reviewing software design patterns. This time out I’m taking a look at structural patterns. These are all strategies for defining and managing relationships between classes and interfaces.

In alphabetical order, they are:

Adapter

The adapter pattern is a good pattern with modest utility. It’s a useful way to reuse third party code. That said, if you find yourself writing adapters between your own interfaces often then something’s probably wrong with your abstractions.

Bridge

The bridge pattern is inherently bad because it relies on inheritance to achieve its objective. What GoF call the “abstraction” must contain a reference to an “implementor”, meaning it must be an abstract class rather than an interface. I don’t see why the so-called “refined abstractions” cannot hold this reference themselves.

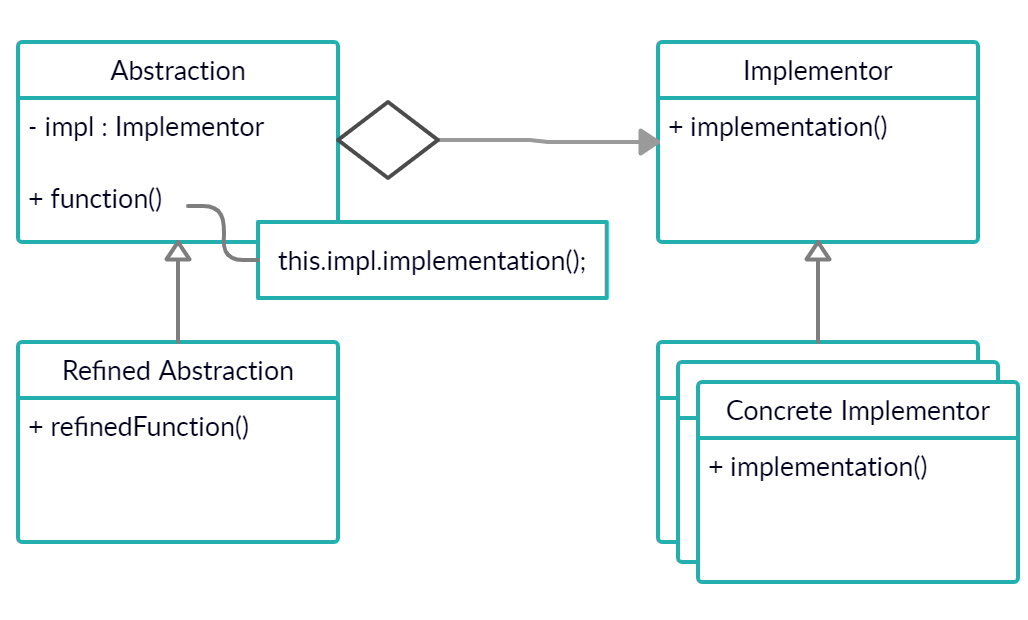

Bridge pattern UML

Bridge pattern UML

By using inheritance you save perhaps 3 lines per class, but you lose the flexibility of a Refined Abstraction deciding that it actually doesn’t require an Implementor instance. Here’s what I’d do instead:

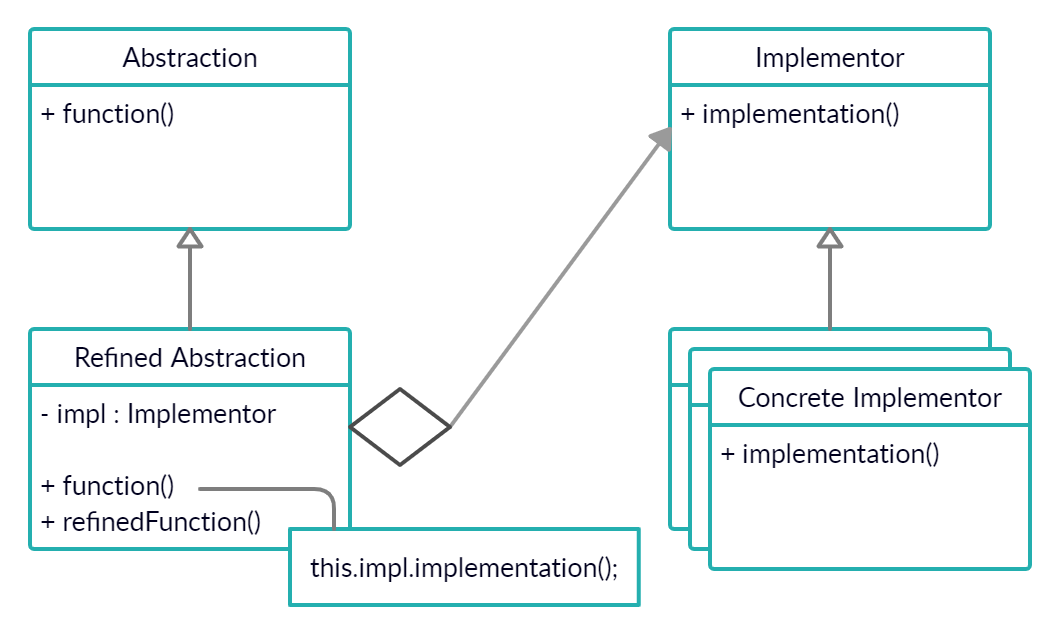

Revised bridge pattern UML

Revised bridge pattern UML

The existence of Abstraction now is largely immaterial. I only kept it to demonstrate the difference more clearly.

I don’t think this is even sophisticated enough to be worthy of the designation “pattern” anymore; it’s just composition and delegation. Apparently someone out there disagrees with me.

Composite

This is a good one for plenty of tree-like structures. Something like a scene graph seems like good use-case. I don’t find too much use for it in practice but it seems perfectly fine.

Decorator

This is easily my favourite design pattern. The decorator pattern allows you to keep classes small and implement behaviour in a composable way. Take this example:

final Request request = new CachingRequest(

new ResponseValidatingRequest(

new HttpRequest("https://www.google.com")

)

);

String body = request.getResponseBody();

Rather than having a single class responsible for making an HTTP request, validating the response and caching the result, the functionality can be split out into one implementation and two further decorators.

The decorators are easy to test because they’re unaware of the underlying transport. If the behaviour needs to change, say to remove the caching, then it’s just a matter of changing the composition at the point of instantiation.

Facade

The goal of this pattern is to “minimize the communication and dependencies between subsystems”, but why do these subsystems exist in the first place? Perhaps several microservices would provide a better delineation between the distinct components.

It seems to solve a similar problem to dependency injection in a less convenient way. That said, I can see some situations where it might come in handy; when refactoring a monolith, employing the facade pattern might be a good first step.

Flyweight

As I see it, this is just a specific form of the object pool pattern. The only distinction is the separation of intrinsic and extrinsic state in order to make objects poolable. It’s just a performance optimization, a workaround for a lack of support for value objects. Avoid it if possible.

Marker interface

This isn’t a GoF pattern but I thought it was prevalent enough to include anyway. The purist in me wants to scream that this is a huge anti-pattern but the reality is more nuanced than that.

Markers should not be used as a limited form of reflection. Where I have found them useful is to provide additional compile-time checks for methods which would otherwise only fail at runtime.

Consider the following example, using Jackson to serialize an instance to a JSON string.

public String getJson(Object obj) {

return new ObjectMapper().writeValueAsString(obj);

}

The writeValueAsString method accepts any Object, so if I want my getJson method to serialize several unrelated

types of messages, I have to declare my parameter as accepting Object too.

The problem here is that getJson can be called with an Exception, a BigDecimal, or a DateTimeFormatterBuilder.

These are clearly mistakes.

If all my messages implement a JsonMessage marker interface, I can change the parameter so that only “whitelisted”

implementations are allowed, preventing possible mistakes.

public String getJson(JsonMessage message) { // marker interface

return new ObjectMapper().writeValueAsString(obj); // accepts Object

}

Arguably, this use of marker interfaces is just a workaround for poorly designed interfaces.

Proxy

This is a good one for the same reasons that the decorator pattern is. In fact, a proxy implementation is likely to look quite similar to a decorator. The book addresses this and suggests that one major difference is in the intent behind the application of the pattern.

I don’t really agree that a different intent means it is deserving of a distinct pattern, especially given that they present multiple variations on a single pattern several times elsewhere. This will become a common theme in the behavioural patterns coming up.